Like the world we inhabit today, the worlds of both the Old and New Testaments were ethnically diverse and richly textured by an assortment of cultures, languages and customs. And also like today, ancient peoples had a number of ways of distinguishing between locals and out-of-towners, friends and enemies, the elite and the marginalized. Prejudice comes in all varieties, yesterday, today and tomorrow.

From time immemorial, humans have held prejudices against others based on their ethnicity, the color of their skin or factors such as where they’re from and how they speak. Since prejudices usually go without being said, in the text of Scripture we are left with gaps in the stories.

In Genesis 27:46, for example, Rebekah exclaims her frustration with Esau’s wives, not because he had more than one, but because of their ethnicity: “I’m disgusted with living because of these Hittite women,” she says to Isaac. “If Jacob takes a wife from among the women of this land, from Hittite women like these, my life will not be worth living.” Rebekah’s comment is heavily laden with ethnic prejudice. There was something about Hittites that sent her up the wall. Most of us don’t know what; it went without being said.

We are prone to fill in such gaps with our own prejudices. This gives us lots of opportunity for misunderstanding. We may assume an issue is due to ethnicity when it isn’t, assume it isn’t when it is, fail to recognize an ethnic slur when it’s obvious or imagine one when it isn’t. Consider these examples.

Stupid Rednecks

Paul had started churches in the southern regions of Anatolia (modern Turkey) in the towns of Derbe, Lystra and Iconium. Acts tells us that on his second sortie into the region, Paul attempted to go into the northern area. This northern region was known by the Romans as Galatia, a mispronunciation of the word Celts, the name of the people group that had settled in the region generations earlier. They were considered barbarians, a term that referred to someone who didn’t speak Greek. The word barbarian was more or less the Greek equivalent of us saying “blah-blah-blah” to ridicule someone’s speech. Since Greeks equated speech with reason (as in the word logos), someone who couldn’t speak Greek was considered stupid.

While the entire region was technically Galatia by Roman designation, the inhabitants of the southern region preferred their provincial names (Acts 2:9-10). They did not want anyone confusing them with those uneducated barbarians in the north. When the churches in this region act foolishly, Paul writes to chasten them. He addresses them harshly: “You foolish Galatians!” (Galatians 3:1). This is roughly equivalent to someone in the United States saying, “You stupid rednecks.”

Paul is employing an ethnic slur to get his readers’ attention. We might assume Paul would never do such a thing; he’s a Christian, after all! Yet that instinct proves the point. Our assumptions about ethnicity and race relations make impossible the prospect that Paul might have used ethnically charged language to make an important point about Christian faith and conduct.

Paul is employing an ethnic slur to get his readers’ attention. We might assume Paul would never do such a thing; he’s a Christian, after all! Yet that instinct proves the point. Our assumptions about ethnicity and race relations make impossible the prospect that Paul might have used ethnically charged language to make an important point about Christian faith and conduct.

We often find it difficult to detect the ethnic dimensions of a situation in the Bible, even when the author is trying to make it plain. Luke, for example, sprinkles ethnolinguistic markers throughout the account of Paul’s time in Jerusalem in Acts 21 (verses 11, 16, 29, 37-40) and 22 (verses 1, 17, 21, 28). In these chapters, Paul was arrested by the Romans during a riot in the temple, but the Romans didn’t know who Paul was. They thought he was an Egyptian who had been causing trouble elsewhere (Acts 21:38).

Why in the world would they think that? We might assume the Roman soldiers were comparing the modus operandi, since that’s how we might go about it. Two riots in recent days? Must be the same guy who instigated both, we might think. But this was not likely their reasoning. They more likely made their judgment on the basis of Paul’s appearance. Jews and Egyptians looked nothing alike. But at the time, Paul was taking part in a purification rite and had a shaved head, as was common in Egypt (Acts 21:24). And to a Roman—well, you know, all “those people” look alike.

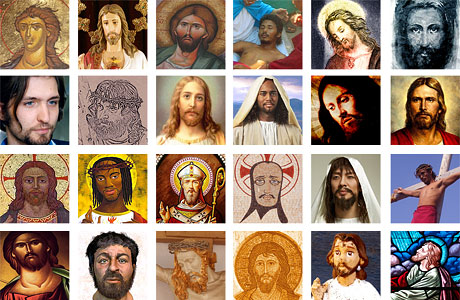

Jesus Had an Accent

One’s accent can often give away where one was raised. This wouldn’t be a problem, except that negative stereotypes are often associated with certain accents. In the United States, for example, a Southern accent may strike you as refreshingly genteel and charming. But you’re just as likely to assume that the person who adds syllables to words and drops their g’s (I grew up huntin’, fishin’ and campin’) is uneducated and slow. The Bible gives us clues that the ancients also discriminated on the basis of how people sounded. Because we can’t hear accents when we read (unless we’re reading Mark Twain), we can miss this form of discrimination in the Scriptures.

In Judges 12, Jephthah rallies the men of Gilead to battle the Ephraimites. Ethnically, the Gileadites and the Ephraimites were related. Both tribes were Semitic, and they shared Joseph as a common ancestor.1 The text suggests that they would have been physically indistinguishable. So after the battle, the Gileadites developed a clever way to identify which survivors were friends and which were enemies. They guarded the fords of the Jordan River leading to Ephraim, and when a survivor tried to pass through, the soldiers made the men say the word shibboleth. The trouble was, Ephraimites couldn’t say the word correctly because they couldn’t pronounce the “sh” sound. If an escaping soldier said sibboleth, they were killed on the spot. That’s pretty serious discrimination.

Our Lord was also easily identified by his accent. Jesus was born in Bethlehem, but most folks didn’t know that. He was raised in Nazareth (Galilee). Since his accent was Galilean, no one considered the possibility he might actually be a Judean (John 7:41-43).When Peter tried to deny his association with Jesus after the arrest, his accent gave him away as a Galilean (Matthew 26:73), and Judeans just assumed that all Galileans would be supporters of Jesus the Galilean. Jewish travelers from all over the empire could identify the apostles as Galileans based on their accents as they preached the gospel during Pentecost: “Aren’t all these who are speaking Galileans?” (Acts 2:7).

Misreading Geographical Stereotypes

Closely associated with the issue of speech are prejudices based on geography. We distinguish among Americans in this way. The terms Yankee and redneck both conjure concrete images and arouse feelings of disdain among certain groups of people. But visitors to new cultures have a difficult time identifying these kinds of distinctions and their attendant presuppositions.

If visitors to a foreign culture have a hard time detecting ethnic stereotypes based on geography, we have an even harder time detecting the same issues in the Bible. We are unfamiliar with the geography of the Near East, as well as the prejudices that adhered to certain locations. Sometimes we do have certain prejudices associated with locations in the Bible. But very often, we have the opposite associations from those of the original audience.

It is easy for us to assume, for example, that Jerusalem was the center of the action in the ancient world. The city was certainly important to the Jews. It was at the center of their eschatological hope. One day everyone would come to Zion, the City of David, to worship the Lord. Because it was central for the Jews, everyone went “up to” Jerusalem, no matter which direction they were traveling from. To us, Jerusalem and its environs comprise “the Holy Land.”

But Jerusalem was insignificant in Jesus’ time. Pliny the Elder (a.d. 23-79), a famed Roman philosopher, statesman and soldier, traveled extensively and described the Jerusalem of Jesus’ day as “the most illustrious city in the East.” That was actually faint praise. We must note well the qualification: that it was the greatest city on the eastern fringe of the empire. This statement might compare to a New Yorker saying, “the nicest town in the backwaters of Louisiana.”

The importance of Palestine was entirely geographic. The taxes were not enough to influence the Roman budget. Palestine was not known for anything except trouble. But that region controlled the only land route to the breadbasket of Egypt and all of Africa. It was important that Rome controlled the land, but the activities that took place there were rarely of Roman interest. Pilate was more the main finance officer or tax collector than anything else.

The events of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection, so important for Jews and Christians at the time, were marginal events in a nothing town on the edge of an empire with more important matters to consider. If we fail to recognize this, we can fail to recognize just how remarkable the rapid growth of the early church really was. For the first couple of centuries, Roman writers often referred to Christians as “Galileans,” indicating how nominal and provincial they considered the early Jesus movement to be.

The events of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection, so important for Jews and Christians at the time, were marginal events in a nothing town on the edge of an empire with more important matters to consider. If we fail to recognize this, we can fail to recognize just how remarkable the rapid growth of the early church really was.

Tips for Reading Well

How do we uncover what goes without being said about race and ethnicity?

Consider Your Prejudices. A first—and difficult—step is making a thorough and honest inventory of your assumptions about people who are different from you. Take time to prayerfully consider your prejudices. Do you harbor bad feelings for members of a particular ethnic group? Or people from a certain sociopolitical group? If you feel brave enough, consider asking your close friends or family whether they hear you make statements or tell jokes about certain people or groups.

Carefully consider why you feel the prejudices you do. Does it have to do with your upbringing? Is it economic—that is, do you make judgments about people based on their appearance or perceived status? Your increasing awareness about your own ethnic prejudices will help you be more attuned to them in the biblical text.

Use a Bible Atlas. Additionally, read Scripture with a Bible atlas handy. Biblical authors don’t often tell us how they or their audiences felt about specific people groups, but they do give us clues by telling us where people are from. Identifying places on a good atlas can help you detect when the author is making judgments based on geography and ethnicity—and when the writer expects us, the readers, to be doing the same thing.

Let the Bible be Your Guide. The narrator may clue you in through repetition that the ethnicity of a character is an issue. This was the case with Moses’ wife in Numbers 12. The book of Ruth provides another example. Ruth is repeatedly identified as “Ruth the Moabite.” That detail lets us know that Ruth’s ethnicity is important for the story.

Note the way the story is told: Boaz confronts the kinsman to ask if he intends to purchase Naomi’s land and is told, “I will redeem it.” Boaz then notes, “On the day you buy the land from Naomi, you also acquire Ruth the Moabite” (emphasis added). The man immediately declines the offer: “I cannot redeem it.” He cites inheritance rules, but we suspect his real motivation is ethnic prejudice. By contrast, Boaz buys the land and states, “I have also acquired Ruth the Moabite, Mahlon’s widow, as my wife” (Ruth 4:4-6, 10, emphasis added).

Next, see if Scripture can shed light on the issue. The Bible is a good resource for determining what the biblical authors and audiences thought and felt about their neighbors. The fact that the Moabites, along with the Ammonites, originated from an incestuous relationship between Lot and his daughters (Genesis 19:36-38) may help us understand why Ruth’s ethnicity is an issue in her narrative. Furthermore, the Moabites hired Balaam to pronounce a curse on Israel (Numbers 22), and Moabite women seduced the men of Israel in Numbers 25 and encouraged them to sacrifice to idols. For these reasons, the Lord declared, “No Ammonite or Moabite or any of their descendants may enter the assembly of the Lord, not even in the tenth generation” (Deuteronomy 23:3). In light of all this, it is truly remarkable that Ruth, a Moabite, is held up as a model of faith and fidelity.

Prejudice is Reprehensible

We have been pointing out the prejudices of biblical characters, but please bear in mind that we are not endorsing prejudice. The Christian message is clear: ethnic prejudice is morally reprehensible. It is wrong. The Roman world was filled with racism. The interior of Anatolia (modern Turkey) was filled with tension between the Romans, the locals and the immigrants (Jews in the south and Celts in the north).

Nonetheless, Paul tells a church caught right in the middle of that mess, “Here there is no Gentile or Jew, circumcised or uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave or free, but Christ is all, and is in all” (Colossians 3:11). This was a radical claim in the first century. It is no less radical today, even in a country in which people have been fighting for equality for decades.

Columnist Jack White once observed, “The most insidious racism is among those who don’t think they harbor any.”2 His point is that those of us who leave our ethnic stereotypes unexamined will inevitably carry them forever, perhaps even pass them on to others. We would add that failing to come to terms with our assumptions about race and ethnicity will keep us blind to important aspects of biblical teaching.

Questions to Ponder

- Imagine retelling the story of Ruth and Boaz today and saying, “Boaz the Israeli” and “Ruth the Palestinian.” How might that affect how you read the story?

- How does it affect your view of Jesus to know that he was born to a people group considered inferior by the majority culture (Romans) and in a town that other Jews considered backward and unimportant (Nazareth)?

Adapted from Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes by E. Randolph Richards and Brandon J. O'Brien. Copyright(c) 2012 by E. Randolph Richards and Brandon J. O'Brien. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, PO Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515. www.ivpress.com

Adapted from Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes by E. Randolph Richards and Brandon J. O'Brien. Copyright(c) 2012 by E. Randolph Richards and Brandon J. O'Brien. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, PO Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515. www.ivpress.com

1The family tree is a little confusing. See Genesis 41:50-52; Genesis 50:22-23 and 1 Chronicles 2:21-23.

2Jack E. White, “Prejudice? Perish the Thought,” Time 153, no.9 (March 8, 1999); 36.